December 16, 2021

Spot the Difference

Full-scale, biologically realistic model of mouse hippocampus uncovers new mechanism for pattern separation – Study published in Nature Computational Science

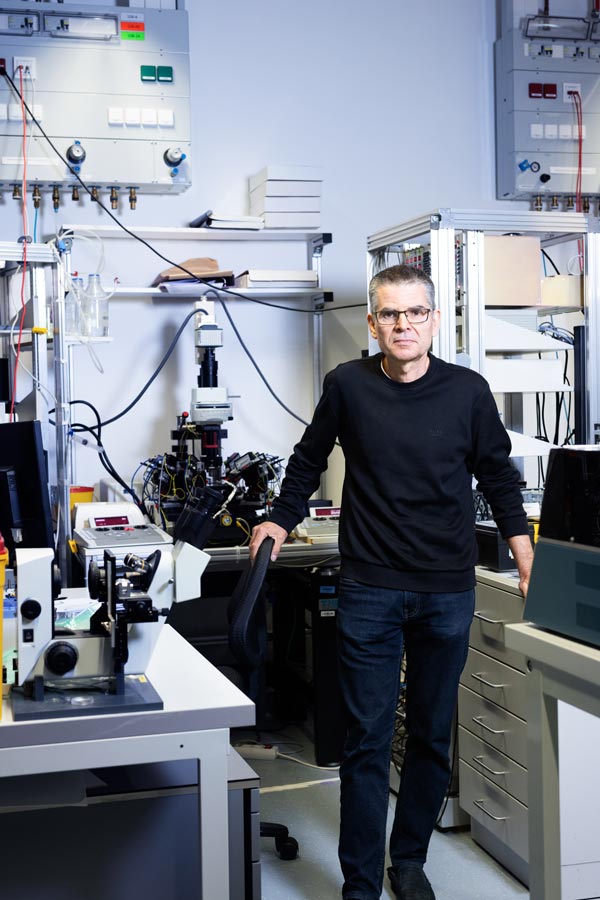

Our brains can distinguish highly similar patterns, thanks to a process called pattern separation. How exactly our brains separate patterns is, however, not fully understood yet. Using a full-scale computer model of the dentate gyrus, a brain region involved in pattern separation, Peter Jonas, Professor at the Institute of Science and Technology (IST) Austria, and his team found that inhibitory neurons activated by one pattern suppress all their neighboring neurons, thereby switching off “competing” similar patterns. This is the result of a study published in Nature Computational Science.

A black cat is deceptively similar to a panther, apart from its size. Making this distinction is crucial when being pursued, and something humans achieve thanks to pattern separation, the process in which the brain distinguishes highly similar patterns and triggers very different behaviors as a response: stroke the cat or flee the panther. This process is also linked to learning. “We need to not just separate similar patterns, but also store and accurately retrieve them, for example for when we next meet a panther. Therefore, we investigated how pattern separation occurs in the hippocampus, a key memory circuit,” says Peter Jonas, Professor at IST Austria and lead author of the study.

500’000 neurons in ne model

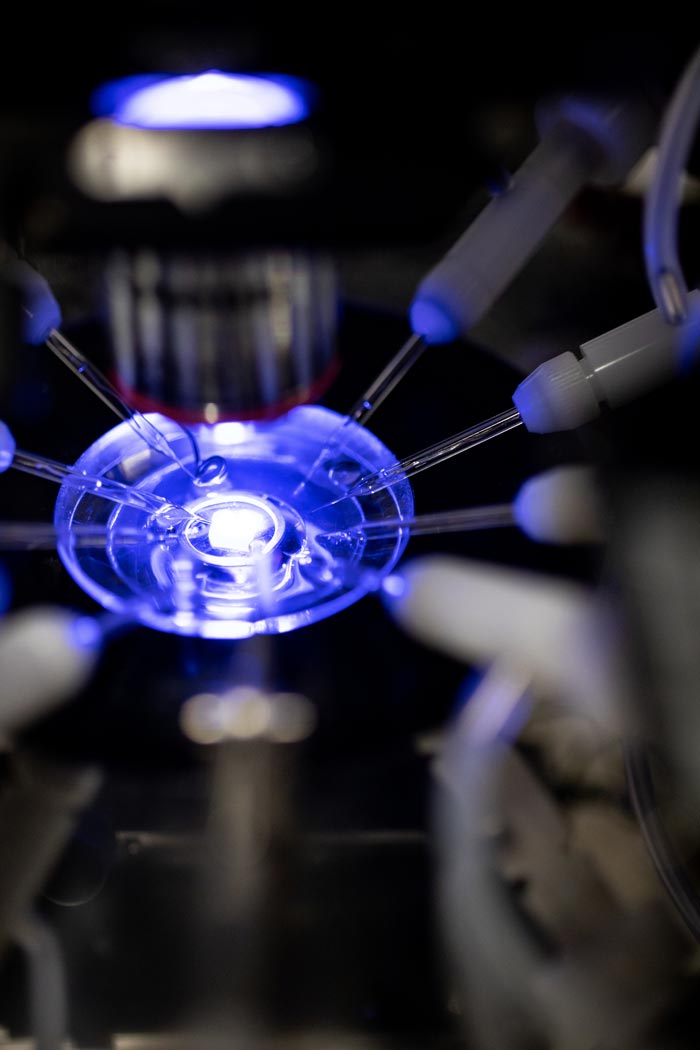

In previous research, Jonas and his team measured crucial parameters of synapses, the connecting points of neurons, and connectivity rules, which are required for understanding information processing in the hippocampal network in mice and rats. In their new study by first author Jose Guzman, the Jonas group used these real-live parameters to build an accurate model of the network – a challenge, as usually, models of brain circuits are built with just 10 to 1.000 neurons. The dentate gyrus of rats, however, contains 500’000 excitatory neurons, called granule cells. “In scaled-down models, we cannot plug in the measured synaptic parameters of the neuronal circuit. But as we wanted to mimic what happens in the brain and use synaptic measurements we obtained previously, we implemented a network in its full size, with 500’000 granule cells.”

Inhibition separates patterns

Using this computer model, Jonas tested different hypotheses of how pattern separation works. “With this model we cannot just copy biology, but systematically change parameters and disentangle factors. This allows us to understand computations in the brain, and how biological factors support or limit computation.”

Historically, based on data from the cerebellum, neuroscientists thought pattern separation is based on expansion: A pattern is projected from a smaller number of neurons to a huge number of neurons in the next layer of processing. This would expand the pattern and make it easier to spot differences. While expansion is a potential mechanism in the cerebellum, it is less likely to be at work in the hippocampus, where granule cells converge on a smaller number of CA3 neurons in the next layer.

“Clearly, expansion can’t be the only mechanism in the hippocampus,” Jonas states. “Evidence from our realistic model suggests that inhibition – active neurons stopping other neurons from firing – plays an important role.” Mathematically, it has been shown that reducing activity in a network makes it easier to distinguish differences between patterns. Using the hippocampus model, Jonas interrogated the role of inhibition. “When inhibition is part of the model, patterns are robustly separated. But when we take inhibition out, this is no longer the case. This modelling data changes the historical view from code expansion to a mechanism based on inhibition.” The new data also explains a result from previous research which has left Jonas puzzled. “Previously, we found that inhibition in the dentate gyrus is locally constrained. Activated neurons only inhibit other cells within a 300-micrometer radius. We have long asked what might be the functional role of such focal inhibition.” The network model shows that such focal inhibition can better separate patterns than global inhibition, in which the entire network’s activity is dampened down. Speed is essential in pattern separation, and focal inhibition reduces delays: Neurons in a pattern switch on and very rapidly inhibit surrounding cells, ensuring that other patterns are not turned on. “It is a cool solution, but not very intuitive, and we could only figure this out using the model,” Jonas points out. As a next step, Jonas plans to transfer results back to the biological system and carry out behavioral experiments, further exploring how inhibition contributes to pattern separation.

Publication

Guzman et al. 2021. How connectivity rules and synaptic properties shape the efficacy of pattern separation in the entorhinal cortex-dentate gyrus-CA3 network. Nature Computational Science. DOI: 10.1038/s43588-021-00157-1

Funding information

The IST Austria project part was supported by funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No 692692, P.J.) and the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) (Z 312-B27, Wittgenstein award to P.J. and P 31815 to S.J.G.).

Animal welfare

In order to better understand fundamental processes, for example, in the fields of neuroscience, immunology, or genetics, the use of animals in research is indispensable. No other methods, such as in silico models, can serve as alternative. The animals are raised, kept, and treated according to the strict regulations of Austrian law. All animal procedures are approved by the Federal Ministry of Education, Science and Research.