September 21, 2021

Hungry Brain Cells

To mark World-Alzheimer’s Day, neuroscientist Sandra Siegert explains how microglia are involved in Alzheimer's disease and how a stroll keeps your brain healthy.

After centuries of being dismissed as insignificant, microglia have become one of the hottest topics in neuroscience. Especially their role in Alzheimer’s disease, which affects up to 38,5 million people worldwide, is discussed controversially. People with Alzheimer’s have increasing difficulty communicating, remembering recent events, and eventually are unable to recognize people close to them. Professor Sandra Siegert wants to understand the mysterious cells, which could lead to new treatments for various disorders, including depression and Parkinson’s disease.

When we accidentally prick our finger, immune cells race to the wound to close it. For a long-time, the researcher thought that this is also what microglia do in the brain: heal wounds and fight off infections. When germs infiltrate the brain, however, the consequences are most often severe. “Only in the early 2000s, people started to realize that microglia also have other purposes,” explains Professor Sandra Siegert. The neuroscientist investigates the role of microglia in the healthy and diseased brain together with her group at the Institute of Science and Technology (IST) Austria.

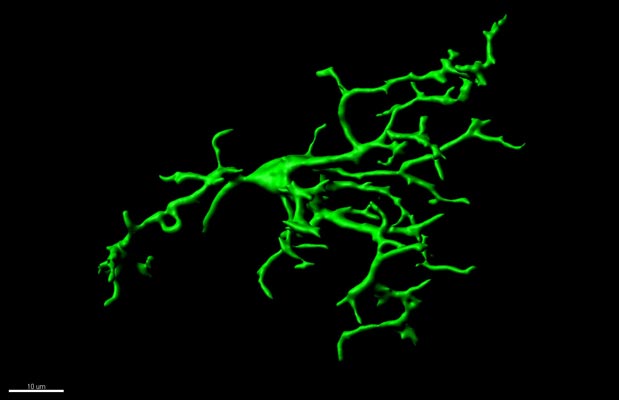

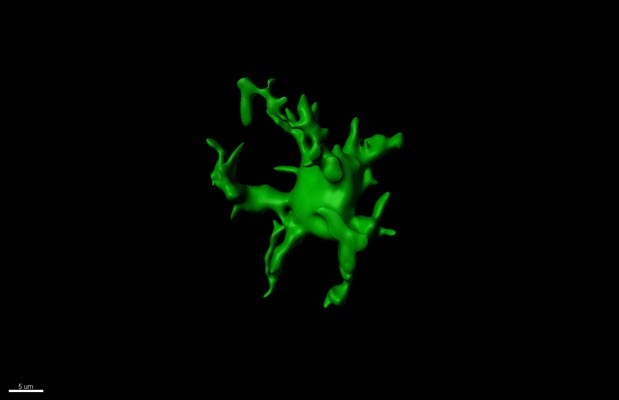

“Microglia can manipulate the connections between neurons, which alters neuronal circuits in the brain,” describes the German researcher who has now worked in Austria since 2015. In the first few years of life, when the brain is still quite adaptive, microglia are primarily found in a reactive state. They tweak pathways in the brain by removing weak connections. Later on, their morphological shape changes, turning from a reactor cell to an observer checking if pathways are functioning correctly.

From rescue to destruction

On the walls of her office, Sandra Siegert collects little post-it notes full of different information on the tiny scavenger cells – a lot of questions remain open. Including whether microglia protect from or contribute to Alzheimer’s disease. “It’s a big debate,” exclaims Siegert. “It looks like they try to stop the disease in the beginning but then there is a turning point at which they begin to destroy the brain.” This happens because the microglia do not react correctly to the body’s signals and break down healthy connections. As a result, people with Alzheimer’s disease experience memory loss, change in mood or behavior, and word-finding problems.

It is easy to distinguish the round, reactive microglia that encapsulate and consume tissue, and the observing microglia, whose extensions stretch through the tissue like roots. The transition between these two states is fluid, however. Determining the time point at which microglia switch to this reactive state and, in the case of Alzheimer’s, become destructive could help develop new therapies. Researchers have therefore created 3D models by imaging microglia from the mouse brain. Using mathematical algorithms, they compared microglia from different time points throughout development and in disease. “We are looking for differences in their shape to be able to determine when a microglia enters a reactive state,” says Siegert about her group’s ongoing project.

Unimaginable Possibilities

Previous studies showed that light flickering with a frequency of 40 pulses per second induces microglia to “eat” amyloid plaques typical in brains affected by Alzheimer’s disease. In a recent study, the researcher at IST could even rejuvenate a brain using a similar technique: When stimulated with 60-Hertz light, microglia induce changes in the healthy brain’s neurons that make them more receptive to new input. Siegert hopes to investigate this further as a potential treatment for depression. But it doesn’t stop there.

Increasingly more research shows that microglia are involved in an abundance of disorders. “Reactive microglia are found in Alzheimer’s, Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Parkinson’s disease, and many other neurodegenerative disorders. The immune system seems to be activated in all cases,” Siegert explains. So, how are they activated? Why do they turn on healthy cells and destroy them? Do microglia behave differently in female and male brains? These are just a few of the questions that Sandra Siegert and her group try to answer. It will take quite a while to understand what goes wrong and how we can treat these disorders, but there are a few things that we can do now to keep our brains healthy.

Preventing Dementia

“Be active, eat well, and think a lot,” preaches the neuroscientist. The risk of getting Alzheimer’s, the most common form of dementia, increases with age. Walking a different way to the shop, learning new things, having new experiences, and interacting with people – those are the things that keep us young. “I have seen this in my closer environment: When someone retires and doesn’t have anything to do anymore, they can fall into a hole, and their mental abilities decline. Thus, I keep telling my grandmother that she should keep herself busy,” recounts Siegert.

The scientist believes that it is best to encourage people living with Alzheimer’s or another form of dementia to carry out as many daily tasks as possible. Although, this may require a lot of patience from caretakers. To challenge her brain, Siegert started learning violin when she was doing her PhD. The music also helps her unwind from stressful days as a group leader in a highly competitive field. “We know that stress is a huge factor when it comes to the brain’s health, and the microglia sense that something is not right,” says Siegert. However, how exactly stress affects our brain cells is yet another question waiting to be answered.